hose of you who are seasoned veterans of camping have likely encountered “hot skin” situations a few times over the years. New RV owners, however, may be surprised and alarmed the first time they touch the side of their RV while standing on the ground and feel a shock. Is this normal? Can it possibly be dangerous?

No, it’s definitely not normal. And yes, it can be dangerous under certain conditions and circumstances. But first, let’s get a few definitions out of the way.

What is “Hot Skin”?

There’s really no formal definition of a hot-skin voltage in the National Electrical Code (NEC). In fact, the phrase “hot skin” is unique to the RV industry. In nearly all other industries and trades it is called a “contact voltage” or “stray voltage.” However, I’ll stick with the term “hot skin” since that’s what the RV industry has been calling it as far back as the 1960s.

What causes a Hot-Skin Voltage?

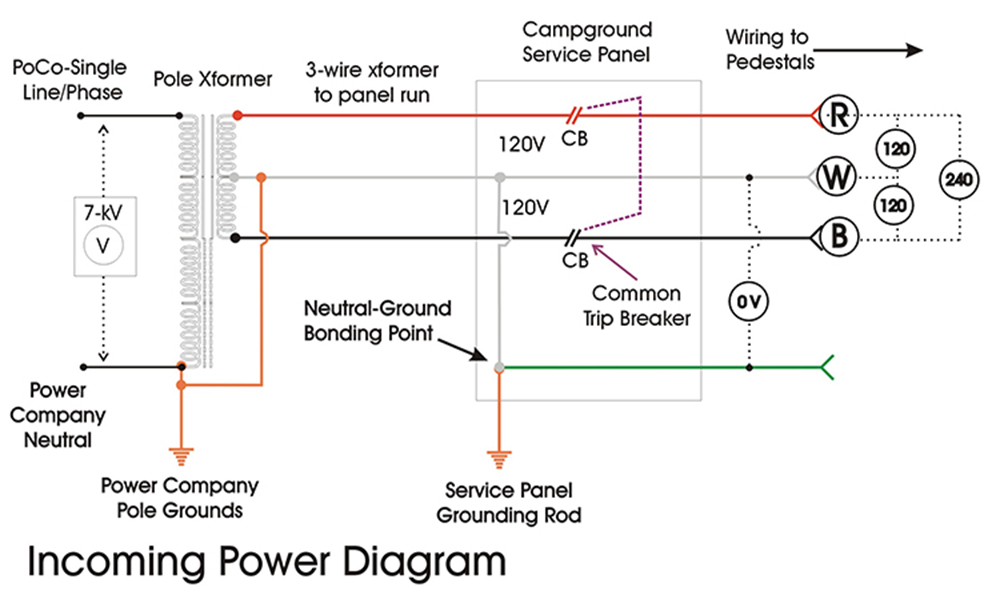

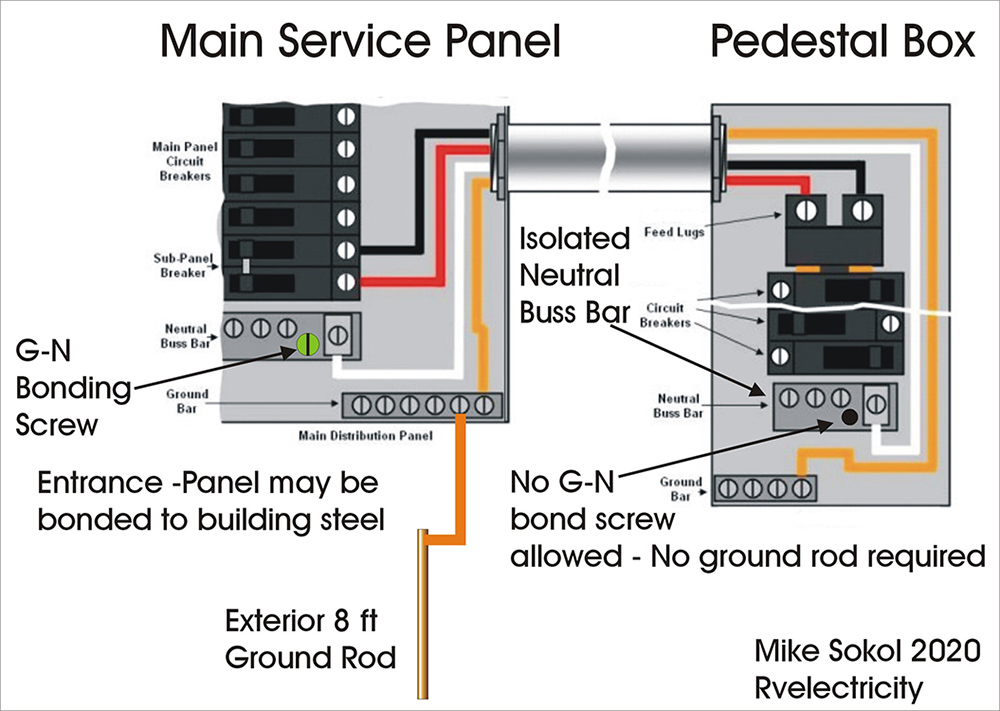

Glad you asked. There needs to be two conditions for a hot-skin voltage to occur: First is a poor or missing ground connection between your RV and the service panel’s ground-bonding point. That means that your RV and all of its shore power cords, adapters, extensions and whatever it’s plugged into (such as the campground pedestal) need to be properly grounded (specifically called “bonded” by the NEC). If your RV is properly grounded to the campground or home service panel’s bonding point, it should be impossible for your RV to develop more than 5 volts between it and earth ground.

Second, you have a source of a ground-fault current, which can turn into a hot-skin voltage since it’s not drained away by the ground wire. Please be aware that a ground rod really doesn’t “ground” an RV (more on that later).

If you feel a tingle while touching any part of your RV, there’s likely at least 20 or 30 volts AC of hot-skin voltage on everything metal — not only is the skin of the RV electrically energized on aluminum-sided models, but the RV chassis is energized as well, along with the wheels, trailer hitch, propane tank/cylinders and even your tow vehicle. That’s because virtually everything metal in and on the RV is tied (or bonded) together. If you have 40 volts on the RV skin, you’ll have the exact same 40 volts everywhere else.

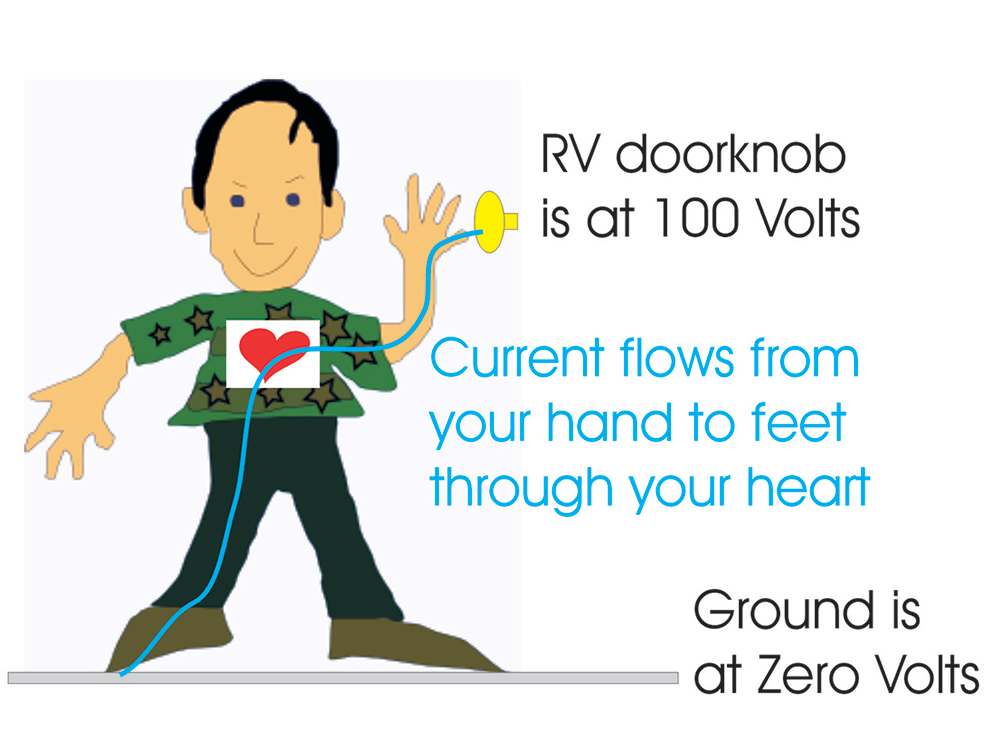

The danger comes when a human body gets between earth ground (standing on the damp dirt, lawn or concrete) and touching anything metal on the RV (such as the steps, door handle, metal skin or bumper). Even the lug nuts on the wheels and the wheels themselves can be dangerous if you touch them while they’re energized and you’re standing on the ground.

If you touch any of these energized parts with your hands or other body part while standing on the ground, there’s a fault current that will pass through your body on the way to ground — and right in the middle of your body is your heart. Depending on your age and fortitude, as little as 10 mA (milli-amperes or 0.010 amperes) of current passing through you can put your heart into fibrillation. If this happens and you don’t receive medical attention in a few minutes, you’ll likely die from this hot-skin shock.

If you measure a small voltage potential between earth ground and the chassis ground of the RV (in the range of 3 to 5 volts), that can be caused by the power company’s unbalanced 3-phase power lines feeding the service panel. This can be annoying but it’s not really dangerous to human life.

However, if you’re measuring 30 to 40 volts — with up to 120 volts AC possible between the RV skin/chassis and earth — then there’s definitely a broken or loose connection somewhere in the RV’s electrical grounding system between the RV chassis and the service panel’s ground-bonding point. In many cases, this can be as simple as a missing ground lug on an extension cord or a worn-out pedestal outlet in a campground that’s too corroded to make a good connection. The campground pedestal in the accompanying example was so worn the park operator had to use a bungee cord to keep the surge protector from falling out of the outlet. Note, too, the lack of circuit breakers — another big code violation.

Making the Connection

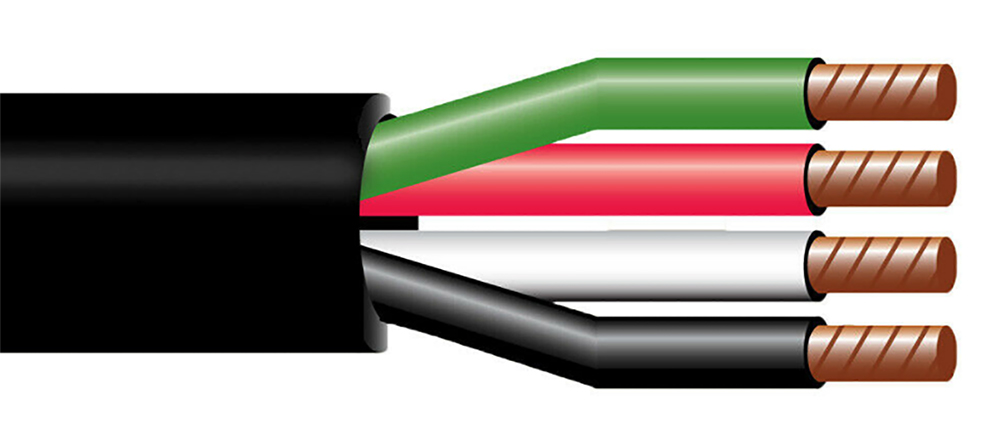

The EGC conductor extends from the bonding point inside the RV’s power panel, though the shore power cord, dog-bone adapter, campsite pedestal outlet and all the way back to the campground’s service panel. There, it’s “bonded” to the neutral conductor of the transformer from the power company as well as at least one (and possibly two) eight-foot-deep grounding rods.

Ground rods are probably not what you think they are. The job of the grounding rod is not to “ground” the RV. In fact, the earth itself is a pretty poor ground, believe it or not. Ground rods are there to direct any lightning strikes deep into the earth before they can take secondary paths through your home or RV wiring. So, a ground rod by itself will not “ground” the RV; that’s the job of the safety ground wire (EGC).

Larger ground-fault currents can also occur in an RV. For the most part, the prime suspects are often the 120-volt AC noise filter capacitors in the RV converter/charger (up to 3 mA), a corroded-through electric water element (up to 2 amperes) or even a dead short circuit between a conductor and the chassis of the RV (up to 20 amperes) which can be caused by something like a screw or nail piercing a wire inside of a wall.

How Do You Measure for Hot-skin Voltage?

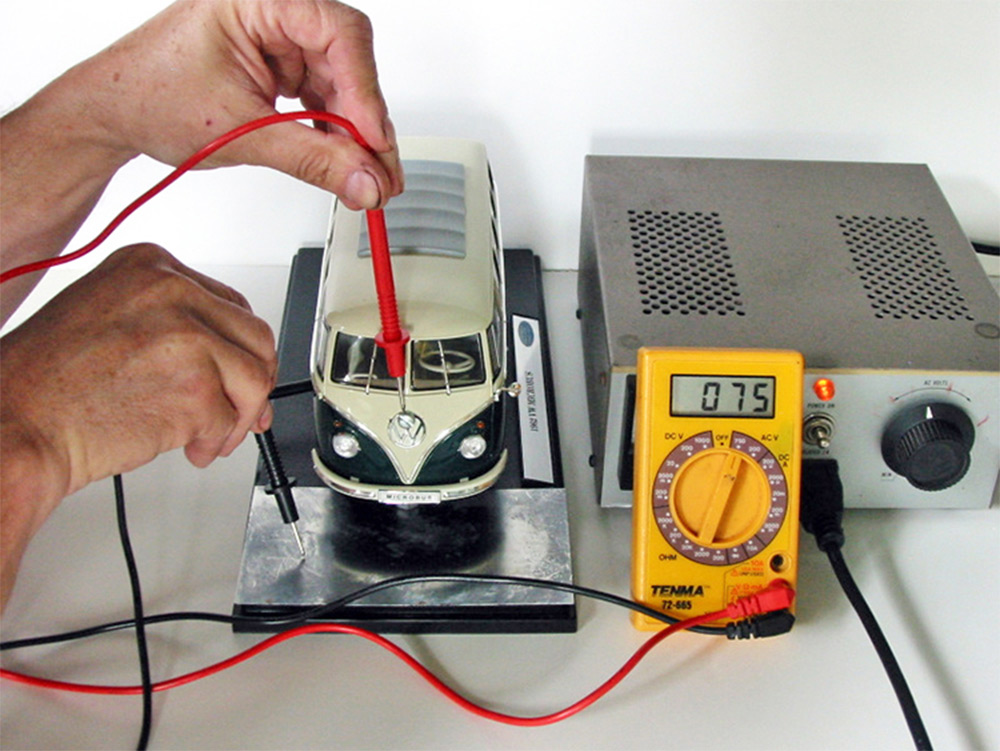

The “gold standard” method to test for hot-skin voltage is to drive a short ground rod into the damp dirt — a 12-inch-long screwdriver will do — and measure between the metal screwdriver shaft and a bare metal spot on the RV chassis. If you measure up to 5 volts AC with a digital meter, there may not be anything wrong at all — but if you find in excess of 10 volts AC with this measurement, then there’s definitely some kind of failure in the RV’s safety ground connection (the EGC in code language).

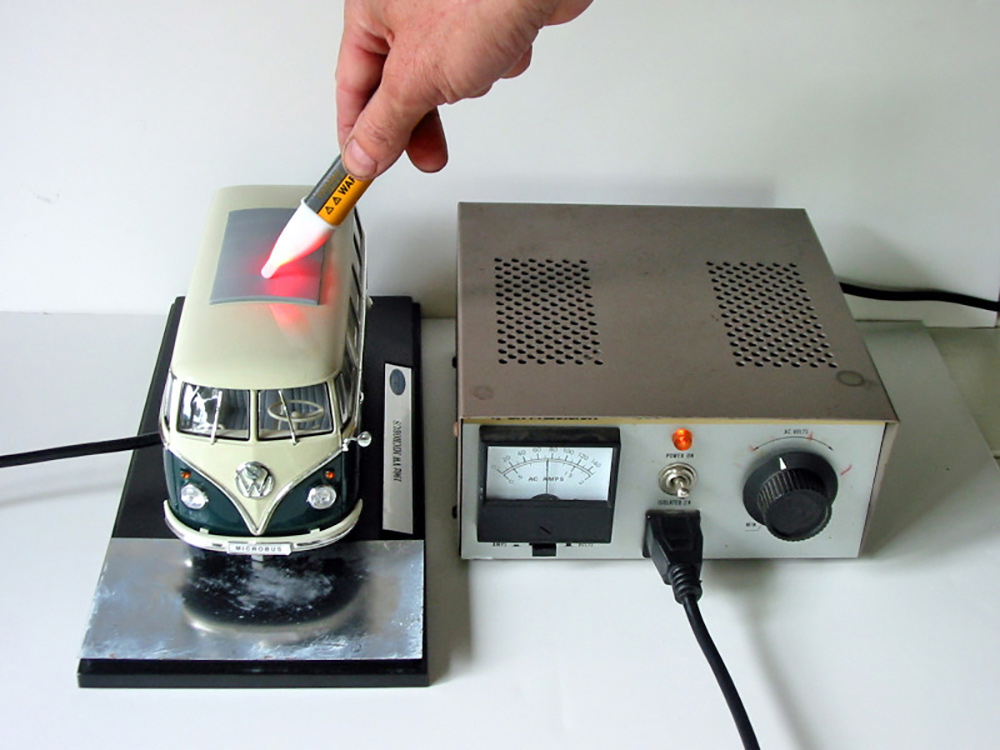

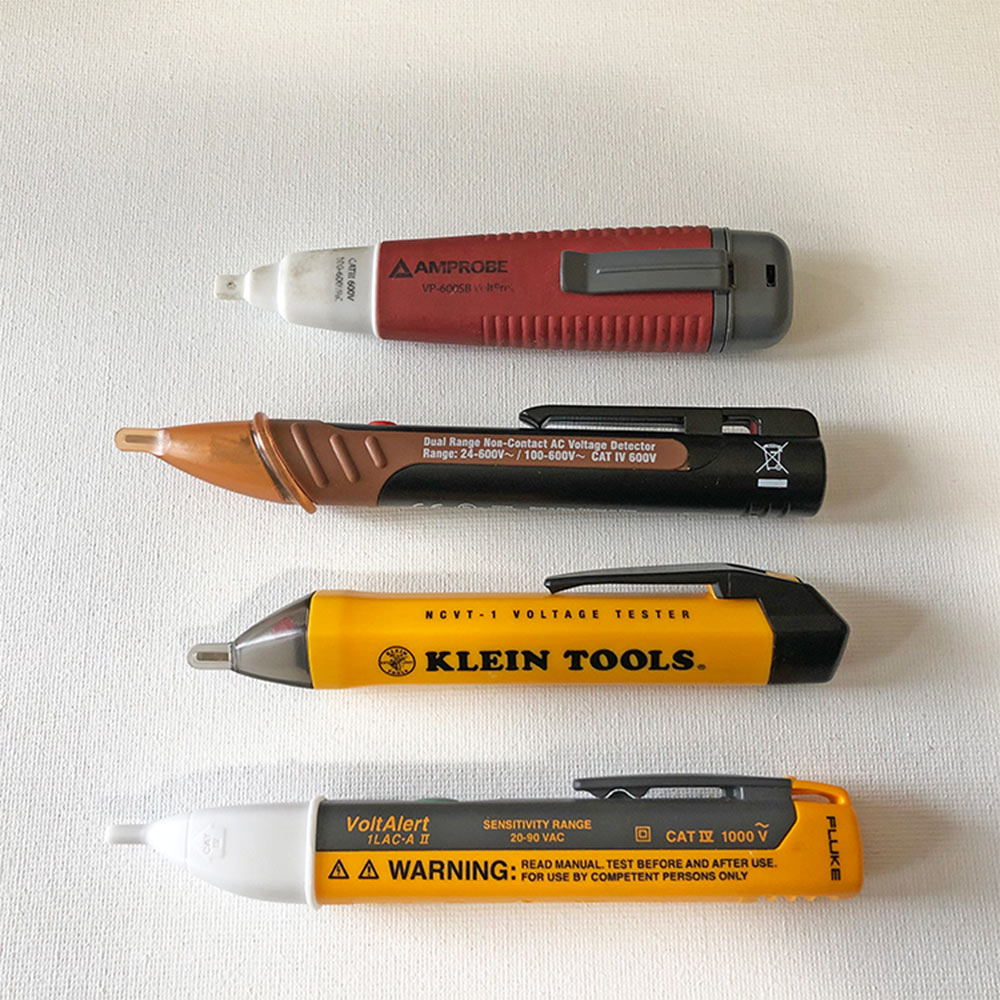

In fact, if your RV has a hot-skin potential of 60 to 80 volts it will typically beep from several inches away — and if your RV has a hot-skin potential of 120 volts AC, it will usually beep from one to two feet away. That should get your attention.

Here’s a basic testing sequence to help determine what is causing hot-skin voltage:

- If you feel the slightest tingle or shock from your RV while standing on the dirt and touching it in any way, immediately power off the pedestal and unplug from shore power.

- Get out your NCVT and test it on a known hot-power source. Turning the pedestal breakers back on and placing the tip of the NCVT in the hot contact will suffice for this.

- Turn off the pedestal circuit breakers, plug in your shore power cord and then test the RV for a hot-skin voltage using the NCVT on normal sensitivity (90 to 1,000 volts). If the NCVT beeps only when making contact with the RV steps, hitch or skin, then you likely have around 40 volts of hot skin. If it beeps from 6 inches away, then you likely have around 80 volts of hot-skin potential. And if it beeps from 2 feet away, then your RV likely has around 120 volts of hot skin.

- Power down the pedestal circuit breaker and retest for hot-skin voltage. If the NCVT doesn’t beep, then the source of the current and voltage is your own RV. If the NCVT continues to beep, then the source of the hot-skin voltage is the campground grounding system, something I call a reflected hot-skin voltage.

- If you have a dual-range NCVT, repeat the test at the 12-volt AC setting. If it beeps when in 12-volt AC mode but not in the standard 90- to 1,000-volt mode, then you have a hot-skin voltage between 10 and 30 volts. This is still potentially dangerous since anything more than about 5 volts above earth ground potential indicates loss of your RV’s safety ground wire (EGC, or Equipment Grounding Conductor) back to the campground service panel ground/bonding point.

- The next test is sticking a long screwdriver (12 inches or so) into the dirt beside your RV and wetting the dirt with a gallon of water if it’s very dry. Now use the AC scale on a digital multimeter to measure the voltage between bare metal of the RV (a lug nut works great) and the screwdriver metal shaft in the dirt. With a properly grounded RV, this should measure below 5 volts. However, it could measure between 10 and 120 volts AC, which indicates a lost ground connection as well as a source of ground fault current. This suggests you can easily develop a dangerous amount of hot-skin voltage.

- Most hot-skin voltages occur due to a break in the RV’s shore power connection, which can be traced to a lost ground contact in an extension cord, dog-bone adapter or shore-power cord itself. Physically inspect all cords and adapter for intact ground pins. You can also measure them for continuity (when disconnected from your RV) using the ohms/continuity setting on any digital multimeter. A surprising number of RV hot-skin conditions are caused by using an extension cord with a broken off ground-pin. Never use this on your RV as it can create a very dangerous hot-skin voltage condition.

- If you find any damage to the shore power connection, replace the broken hardware and test again. If it now shows the voltage has returned to less than 5 volts, your ground connection is secure. But, you could still have a mid-current ground fault source.

- Test for a ground-fault current over 5 mA by using a dogbone adapter to plug the RV into a GFCI receptacle. If it doesn’t trip the GFCI, then you likely have normal ground fault leakages of under 5 mA. If it does trip the GFCI outlet, then you have a medium-current ground fault source, most likely a corroded or melted water heater element that should be replaced immediately. If plugging in trips the 20-amp circuit breaker, then you have a high-current ground-fault in your RV, likely caused by a pinched wire or a nail, screw or staple that has pierced the wire insulation.

Well, don’t leave your RV plugged into power and hope for it to go away. You need to unplug from shore power immediately until you or the campground operator locates the source of the voltage and repairs it.

You may feel a stronger tingle if the dirt is wet — and it may even seem to go away when the dirt dries out — but that usually doesn’t mean that the hot-skin voltage has magically disappeared. What probably has occurred it is that you’re now in dry shoes standing on dry ground, so there’s so little current passing through your hand that you can’t even feel it as a shock. But the hot-skin voltage — and the potential fault current causing it — in all likelihood has not gone away. It’s probably just disguised by the dry dirt. The next time it rains, the real danger lurks if anyone touches any metal part of the RV while standing in a puddle outside.

Above all, if you suspect that you are experiencing a hot skin condition, unplug the RV from shore power and either diagnose the issue yourself or arrange for a professional to help you as soon as possible.

The good news? Even if you find a hot-skin condition, it can be rectified!

Other appliances with a grounded, three-prong plug may have line-to-chassis leakage currents of up to 3.5 mA (milliamps) and still be within NEC and UL guidelines. Let’s call this a Low Current Leakage. The round prong or pin on the 120-volt AC plug is the “safety ground contact” which must have a low-resistance (impedance) path back to the service panels G-N-E (Ground-Neutral-Earth) bonding point to be effective.

An appliance with a partial-shorting failure (such as a hot-water tank with a break in its hermetically sealed electric element) will leak 1 to 2 amperes of fault current from the AC line to the water supply (and your RV chassis). Let’s call this a Mid-Leakage Current.

An appliance or wiring box with a dead short between the line and the chassis (such as a pinched wire or a screw driven into the wall, which penetrates the wiring insulation), can provide full circuit breaker current between the line and the chassis, up to 20 amperes. Let’s call this High-Leakage Current.

If that appliance chassis is bonded (connected) to the RV’s safety ground with a proper low-resistance (also called impedance) connection, and the RV’s safety ground (and chassis) is properly bonded to the G-N-E connection back at the entrance service panel, then all of the above fault currents will be returned back to the service panel (and the transformer on the pole) and be rendered harmless. Note that these fault currents do not return to the earth beneath your feet through the ground rod. A service panel ground rod’s job is to protect the system from lightning strikes and help maintain the local ground plane’s voltage close to earth potential.

What does this all mean in the real world?

The Very Low (0.75 mA) and Low (3.5 mA) Leakage currents will be easily drained away without you even knowing about it, probably without even tripping a GFCI you should be plugged into. These ground fault currents are all within UL and NEC allowed leakage values and are quite normal.

A High-Current Ground Fault (20+ amps) should trip any circuit breaker instantly by returning the fault currents back to the service panel’s G-N-E bonding point. A properly grounded RV will not develop a hot-skin under this failure condition since these High-Current faults should still be drained to the service panel’s G-N-E bonding point, thus tripping the circuit breaker.

Secondly, the ground rod really has nothing to do with getting rid of these ground-fault currents. A ground rod connected to your RV or the campground’s power pedestal will not provide a low-resistance ground fault path and will allow hot-skin voltages to exist on your RV. And simply lowering the leveling jacks on the dirt definitely will not ground an RV.